I’ve been saying it for years and I’ll keep on saying it. If you want to stay healthy, keep away from doctors and hospitals.

Almost everyone now, I think, understands the latter of the two. HOSPITALS ARE THE WORST PLACE ON EARTH FOR HEALTH. How ironic, when we depend on them so much to get well when we are particularly sick.

But starting with “flesh eating bacteria” (a nonsense media scare label), in other words MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus), people have begun to realize that hospitals are not so much about sterilization and hygiene, as about gathering together all the foul pathogens in one place!

That’s what makes hospitals dangerous. OK, time was when enough soap and water, plus Chlorox or Dettol, and the hospital at least smelled clean. But as staffing costs went up and economies were made, the same high standards were not being met.

Doctors and nurses got lazy about washing their hands (no, really—but it’s better now, after science showed that washing our hands helps prevent the spread of infections).

Nobody was much concerned, because we had antibiotics which did the job. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed like antibiotics were not so successful as they once had been. The word “resistant” began to tremble on our lips!

In time, infections acquired in hospital went on a dramatic rise. And these turned out to be pretty nasty microbes. Many were very dangerous and resistant to just about all the usual agents.

In 2019, the World Health Organization listed antimicrobial resistance as one of the top ten threats to global health. The agency’s fear is that humanity is returning to a time when easily treatable infections—such as tuberculosis and gonorrhoea—can no longer be kept under control.

The global overuse of antimicrobial drugs on farm animals and in human medicine has been pegged as a cause for the emergence of widespread antibiotic resistance. Agriculture more than abuse by doctors, really.

We began to hear the word “superbugs”. MRSA was just the first among many. Now we have carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae or CRE, Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB), Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Then we had Clostridium difficile; very difficult to kill, hence the name. Yet it wipes out a patient’s nice friendly microbiome. It’s like letting a shark into your fish pond!

Plus: along came an even more deadly form of MRSA which is diabolically resistant to treatment and carries up to a 50% mortality.

Which ever way you cut it, the Golden Age of Antibiotics is over. The 60-year window of safety is closing fast. Thousands die every day of infections that are no longer responding to antibiotics.

Something New

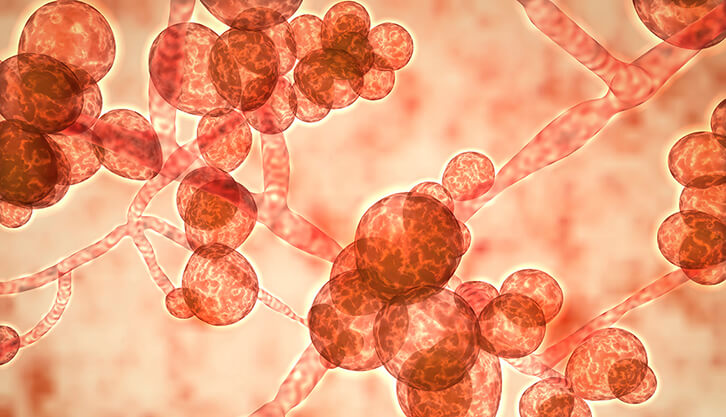

Against this gloomy background, we have a new assassin to worry about: Candida auris. Yes, it is a Candida, a kind of yeast. But it’s much more deadly than its cousin Candida albicans, the cause of common thrush (itchy white plaque in the mouth or female genitals).

C. auris can rampage through an institution such as a hospital, without anyone being aware it’s there and that they are being overrun by the enemy. Over the Christmas break, 2015, this new superbug yeast was found by a doctor working at the Royal Brompton Hospital, in London, the largest heart and lung center in the UK. It was already spreading through the intensive care unit, despite strict protocols to prevent infections.

Dr. Johanna Rhodes, an infectious disease expert at Imperial College London who studies antifungal resistance, was brought in. What she saw stunned her: “You think COVID-19 is bad until you see Candida auris,” she is quoted as saying to National Geographic magazine.1

C. auris has spread to at least 40 countries where it’s been tied to deaths in 30 to 60 percent of cases. A study published 2018 in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases found 45 per cent of patients died within 90 days of being diagnosed with the infection.2

By comparison, the coronavirus kills only about one percent of those infected.

C. auris can evade drugs made to kill it—and early signs suggest the COVID-19 pandemic may be propelling infections of the highly dangerous yeast. That’s because C. auris is particularly prominent in hospital settings, which have been flooded with people this year due to the coronavirus.

The superbug sticks stubbornly to surfaces such as sheets, bed railings, doors, and medical devices—making it easier to colonize skin and pass from one person to another. Moreover patients who have tubes that go into their body, such as catheters or ones for breathing or feeding, are at the highest risk for C. auris infections, and these invasive procedures have become more common because of the respiratory failure associated with COVID-19.

Last year, the CDC classified C. auris as one of the biggest drug resistance threats in America. Now, though it’s too early to confirm a direct knock-on effect, the U.S. has recorded 1,272 confirmed cases of C. auris in 2020 alone, a 400 percent increase over the total recorded during all of 2018, the most recent year with available data.

The real number is likely to be much higher, though, as the COVID-19 pandemic has halted much of the disease surveillance for C. auris at hospitals and because the germ can often colonize a person’s skin without generating symptoms.

It’s ironic: medical staff have been messing around trying to “contain” the really mild COVID-19 virus, and ignoring a deadly killer. It doesn’t make sense. But then there is no science or proper risk assessment in this narrative.

Treatment?

The biggest surprise was that all the specimens of C. auris were resistant to fluconazole (Diflucan)—the first-line drug for treating a variety of fungal and yeast infections. In fact we have learned that C. auris is nearly always resistant to this medication and the chemical relatives in its family—known as azoles. Some variants are also impervious to the other two main classes of antifungal drugs.

The optimal treatment regimen for C. auris has not been decided. Because the majority of C. auris isolates identified in the United States have been susceptible to echinocandins, treatment with a drug from this class, along with infectious diseases consultation, is suggested for initial therapy.

Treatment of colonization without evidence of active infection is strongly discouraged3. Close monitoring for treatment failure and the emergence of resistance upon treatment is required.

Tracking deaths due to deaths caused by this superbug often complicated because the germ tends to be acquired in hospitals among people who are already sick with something else. Doubtless many—perhaps very many—C. auris deaths are attributed to COVID-19.

The new superbug may also be contributing to the tens of thousands of excess deaths occurring during the COVID-19 era. Hence why doctors around the world are sounding the alarm.

Lies always make effective answers difficult.

Obviously, preventing C. auris infection in the first place is ideal.

I repeat: just stay away from harm if you can (meaning doctors and hospital).

Meanwhile, you might want to check out my encyclopedic book How To Survive In A World Without Antibiotics, because that’s the way it’s going!

To your health and freedom,

References:

2. WARNING: Killer fungal infection ‘sweeping the globe’ Sunshine Coast Daily, 9th Apr 2019

3. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/c-auris-treatment.html