Angiostrongylus cantonensis, also called “rat lungworm,” was first discovered in southern China in the mid-1930s. It’s a foodborne potentially-fatal parasite that can invade human brains. Uuggh! It has spread relentlessly and today it inhabits tropical islands and warm, humid areas of five continents, including right here in the USA. Although rats are the parasite’s definitive host, humans most often fall ill after ingesting infective larvae within snails and slugs, many of which are locally invasive species.

A classic example is the Asian semi-slug Parmarion martensi. Ever since it was first identified on Oahu in 1996, on the Big Island in 2004, and on Maui in 2017, P. martensi has often entered human habitats bearing heavy larval loads. Once inside humans, those same larvae head for the central nervous system where they typically grow and die, sometimes leaving deadly inflammation and neurologic harm in their wake.

Standard treatment is an anti-helminthic drug called albendazole (Albenza). But it needs starting right away and often there is a delay in diagnosis. Many illnesses due to A. cantonensis go undiagnosed or are never reported. Even so, in 2019, there were 9 cases identified among local residents and visitors to the Big Island of Hawaii.

The bad news is that, every year, millions of people visit Hawaii (including Vivien and me!), most knowing nothing about rat lungworm, including answers to such basic questions as: How can I avoid it? How is it eradicated? What are the early symptoms, to alert me to trouble, and allow me to receive prompt, effective treatment before developing nasty complications?

Most doctors are pretty ignorant of these issues too!

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a nematode or flatworm.

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a nematode or flatworm.

Illustrative Case

As an example of how subtle and sneaky parasites can be (they invade when tiny and invisible and then grow!) a 56-year old woman from Seattle who, after nearly 2 years of COVID restrictions and being shut away, couldn’t wait to enjoy some warm sun and the balmy trade winds in Hawaii. Unaware of any possible danger, she ate several salads and a veggie wrap during her 8-day stay on Hawaii Island in December 2021.

Her early symptoms—a strange tightness in her chest and sporadic tingling—began even before she left Hawaii. Back home she began suffering myalgias (muscle pain), burning pains, and a rash on her body. It got worse. Shortly afterwards she began experiencing altered vision and unsteady balance.

Not surprisingly, it was several weeks before the doctors’ index of suspicion was sufficiently high that they did a spinal tap and sent a small sample of her cerebrospinal fluid to the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases at NIH. There, an ultra-sensitive test for A. cantonensis DNA proved she had contracted the “rat lungworm”. Unfortunately, her brain was already injured. Even 3 months later—despite 2 weeks of albendazole and ongoing treatment with another drug, Decadron—the once-athletic social worker still had double vision and an unsteady gait.

Brain damage is celebrated with the wonderful expression “neuroangiostrongyliasis” and symptoms may include severe, unremitting headaches, migrating numbness and even paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction due to inflammation in the spinal cord, hydrocephalus (fluid pressure inside the skull), and, eventually, coma and even death.

How Does This Hideous Thing Even Exist?

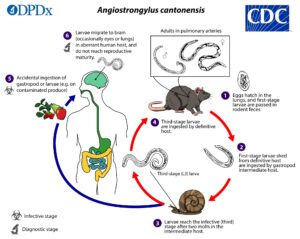

All parasites have a growth sequence called the “life cycle”. Rat lungworm’s revolting life cycle was first clarified in the 1950s and 1960s. In summary: adult A. cantonensis worms live and mate in rats’ pulmonary arteries, fertilized eggs hatch in the rats’ lungs, and baby larvae travel upwards to the back of the mouth, are duly swallowed, and thus pass in rats’ feces. After snails and slugs eat those feces and their larvae mature, the cycle begins anew when a new gang of rats eat the mollusks.

Ironically, humans are of no use to this parasite: it can’t complete its life cycle in us. We are just a side line, as you can see (in blue) from the CDC chart. Nevertheless, this is a dangerous pathogen.

So when did people enter the picture? In the first few decades following rat lungworm’s discovery, most human cases (often presenting as eosinophilic meningitis) were linked to eating raw or undercooked freshwater snails or prawns. In the 1960s, however, research in Hawaii and Polynesia suggested that fresh leafy greens, hiding snails or flatworms, could also transmit infection.

A famous outbreak in 2000, in which 12 medical students from Chicago suffered rat lungworm meningitis after sharing a large Caesar salad in Jamaica, left no further doubt that uncooked produce could also transmit the neuro-invasive nematode.

A New Global Parasite

This needs taking on board. There’s a new nasty kid on the black… and I do mean NASTY.

Rat lungworm has spread to most parts of the globe, almost unopposed (today, the parasite happily thrives in Southeast Asia, the Pacific islands, Japan, Australia, South America, the Caribbean, and the southeastern U.S. as well as parts of Africa and the Canary and Balearic Islands). We all know the importance of eating fresh greens, salads and fruits. But you must be careful from now on. Be alert to what may be on, in, or under your food! There is a need to balance healthy eating against genuine foodborne hazard now prevalent in these and other endemic countries.

Fortunately, thorough washing of produce removes infected A. cantonensis-infected mollusks, even though they may be very tiny; cooking and freezing outright kill larvae; and early treatment mitigates illness. But you must be cautious and aware if you are travelling to these areas. And do help by sharing this knowledge with others who may travel there, or who are at risk. If nobody warns them, how will they know?

Here is a summary of possible symptoms but remember, ANYTHING is possible with parasite disease. These guys are eating you alive and it depends on which bit of you they start with!

Fatigue

Skin rash

Nausea

Itching

Low grade fever

Diarrhea

The liver, the heart and lungs are attacked. The worms are moving around inside YOU. They walk through you, like your body is a highway to them. Very creepy.

But it’s when they get to your brain and spinal cord that really bad problems start. The worms nibble on parts of the brain and nervous system. The results are varying degrees of neurological damage, such as headache, weakness, stiff neck (like meningitis), bladder dysfunction, sensitivity to light and even loss of consciousness. Your brain feels like it has just been hit in a bad motor smash.

This may lead easily to the need for intensive medical support. The patients can be incapacitated, non-compos mentis, unable to move or speak and needing respiratory support.

Often the patient is left permanently disabled; they cannot work again; and financial ruin awaits; or at least dependency on community support. Lives are altered forever.

COVID? What a joke. This rat lungworm misery is real and is under-reported, not blown up with inflated false statistics!

And you know what? Nematode worms are not going away. It’s been said that if you removed everything on earth except nematode worms, you would still be able to recognize forests, hills, rivers and ocean shores, animals and plants; even human habitations.

To learn more about parasites and how to protect yourself against possible harm, get my book.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE PARASITES HANDBOOK!

To your good health,

Prof. Keith Scott-Mumby

The Official Alternative Doctor

I am indebted to Dr. Claire Panosian Dunavan, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, for much of this knowledge. She has recently produced a documentary about rat lungworm disease, called “Accidental Host—The Story of Rat Lungworm Disease,” which will air later this year.