We have thousands, or even millions, of body clocks. Learning to control them, it is said, will solve problems from jet lag to weight loss. We now have a field called chronobiology (time and biology) and a spin off called “chrononutrition” (timed eating as a means of controlling appetite and weight loss).

More on that later.

Not so long ago we thought that the body clock was a one-off control mechanism, housed somewhere in the brain. No longer. We now know our bodies contain thousands, if not millions, of independent clocks that subtly control the functioning of our tissues and organs from the brain and heart to the lungs and liver.

These clocks mean that not only are there benefits to eating regularly but that different parts of the body are tuned to work optimally at certain times of the day. When these clocks fall out of sync it can have serious consequences.

Conversely, if we learn how to take advantage of these rhythms we could be on a fast track to everything from slimmer waistlines to more effective treatments for cancer.1

The History of Circadian Rhythms

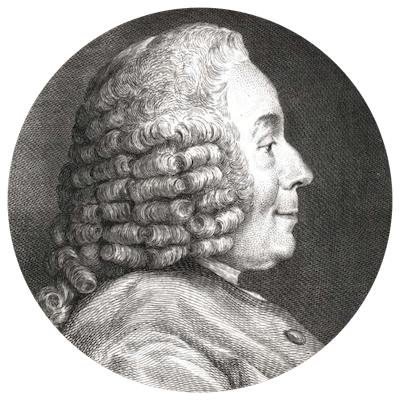

The first written report of circadian (daily) rhythms came about 300 years ago when a French astrophysicist, Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan (1678-1771), showed that, when placed in darkness, some plants continued to open and close their leaves with a rhythm of about 24 hours. (Mairan, incidentally, lived to the great age of 92).

The word circadian comes from the Latin circa diem (meaning “about a day”).

Eventually in the 1970s researchers looking for the seat of biological rhythms in mammals figured out that a small part of the hypothalamus directly behind the orbit, tracked light and dark signals coming in from the eye to keep the body in time with day and night. These areas send signals around the brain and body to control things such as hormone release, the regulation of body temperature and appetite.

It was many more years before gene studies revealed the startling fact that this clock isn’t the only one.

In fact, “The functional activity of almost half of mammalian genes varies regularly with time,” said John Hogenesch of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. In 2014, he published an atlas of these so-called “circadian genes” across 12 organs in mice, showing how the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, skin and fat cells, among others, function over the course of a day.2

Perhaps the biggest surprise was that the outside signals controlling the timing of this frenetic genetic activity didn’t necessarily come from the brain. “Put a liver cell in a petri dish and it very happily ticks along at its rhythm of about 24 hours,” says neuroscientist Frank Scheer of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.1

According to Jonathan Johnston at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, the idea of a single “body clock” is clearly wrong. It’s now obvious that the human body has a complex network of thousands or millions of clocks all over the body, all doing their own thing and all of which have to talk to each other and synchronize to each other.1

Body Clocks and Weight Control

In 2000, a seminal paper revealed that, in mice, you could uncouple the peripheral clocks from the central pacemaker simply by changing the time at which they ate. If the mice could only eat during the day, when they are usually asleep, their peripheral clocks shifted by 12 hours, but the central, light-activated brain clock remained the same. The liver was the fastest to adapt, taking three to four days, but after a week the heart, kidney and pancreas had shifted too.3

But it was even more interesting than that: the mice that had their eating times disturbed, or their core clock genes disabled, were more likely to gain weight and acquire fatty livers. This has awesome inference for dieting and weight loss!

Think of it! You eat a food at a certain time of day and gain weight. Eat the same thing at a different time and nothing happens. You remain steady! A cheeseburger in the morning is one thing; late at night it could be wicked in its effects.

The bad news is that studies show that adults who eat their meals at irregular times have a greatly increased risk of metabolic syndrome, which includes cardiovascular problems and diabetes decades later.4

And it’s not just about metabolism. For instance, the heart experiences a burst of activity first thing as our bodies prepare for the rigors of the day, as do other organs. We are also privy to a surge of the stress hormone cortisol in this pre-dawn rush hour, which may explain why things like heart attacks are so common first thing in the morning.

Taken together, the findings not only cast longevity in a new light, but may also explain the higher prevalence of conditions such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular problems among regular night workers.

So What Is Chrononutrition?

Created in 1986 by French nutritionist Dr Alain Delabos, chrononutrition is more than just a diet: it’s a whole new way of eating that follows the body’s natural rhythm and enzymatic secretions.

You eat foods at times of the day when they are most useful, to meet your body’s energy requirements and prevent storage of food as fat in certain parts of the body.

According to Dr Delabos, humans’ natural ancestral needs are predetermined in the body.

The body secretes different substances (enzymes and hormones) to break down the different types of food we eat, in a scheduled and organized way.

Chrononutrition works by calculating the body’s enzyme secretions and works out what foods to eat at certain times and what to cut out at other times.

There are no forbidden foods, no calorie counting and no fat or sugar control. You lose weight the French way: without deprivation!

This method emphasizes breakfast and lunch, which tend to be neglected. Lunch and dinner should consist of a single dish. Wine and desserts are allowed twice a week (two cheat meals, that is, not two cheat days).

In practice: I got this outline regimen from a passionate supporter of the “plan”.

- A big breakfast

What to eat: Breakfast should be hearty and include fat! (ie: 3.5 oz. (100g) cheese or ham, 2.5 oz. (70g) bread, 3/4 oz. (20g) butter and a hot drink without milk or sugar). Black coffee and a ham and cheese croissant would be just perfect!

Why: Every morning the body secretes 3 key substances: insulin, to receive sugar the organs need to function from the moment we wake; lipases, to metabolize fats used for the production of cell walls; and proteases, to metabolize proteins used to produce cell content. Fats kill the appetite.

- A good lunch

What to eat: 8 oz. (200g) of fish or meat (any) or 2 eggs (omelet, boiled, etc.), with 1 small portion of carbs (pasta, rice, mash or bread).

Why: At midday, proteases are secreted to put in place cellular protein and to stock protein reserves.

- Sweet afternoon tea

What to eat: 1 oz. (20g) dark chocolate or raw or dry roasted nuts, or 1 small bowl of olives, or one small bowl of dried fruit (raisins, apricots and prunes).

Why: In the middle of the afternoon, you experience a peak in insulin which aims to use sugar in order to compensate for fatigue linked to organ function.

- A light dinner

What to eat: Lean fish or seafood, or 4 oz. (120g.) white meat without sauce and 1 small bowl of vegetables, dressing optional. NO CARBS.

Why: In the evening, there are hardly any digestive secretions except those that slow down the breakdown of food.

As they say: Timing is everything! Good luck if you want to try it.

References:

-

New scientist Magazine issue 3069 published 16 April 2016

-

PNAS, vol 111, p 16219

-

Genes and Development, vol 14, p 2950

-

International Journal of Obesity, vol 38, p 1518